After 8 hours bouncing around on a small boat, 40 miles offshore, freezing & wet from sea spray, finally…. frigate birds. And when we reach the birds, there’s splashing from below. The frustration, boredom & sunburn is about to pay off. 3….2….1….GO! GO!! GO!!! And just as I drop into a writhing mass of chaos with sea lions, mahi, and 10,000 sardines, a whale crashes the party and swallows 99% of the baitball in one massive gulp.

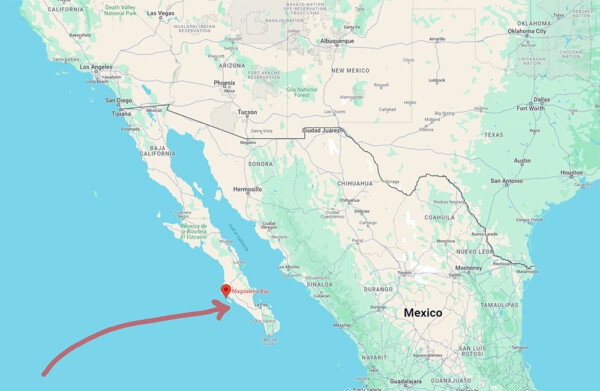

And that’s pretty much how it went for 10 long (very long) days. But let’s back up. Magdelina Bay is on the Baja Peninsula of Mexico, so getting there from Fort Lauderdale was via Houston to Cabo, then a 3-hour bus ride to La Paz where we met our guide, and then another 3-hour drive to the sleepy little town of San Carlos in Magdalena Bay, where I went straight to work unpacking the snorkeling gear and assembling my camera housing in our very basic, yet comfortable 2nd story room. The anticipation & excitement for tomorrow’s shoot was easily overcome with exhaustion from 14 hours of travel, the mental stress of dealing with the well-known, yet often unavoidable Mexican customs scams that particularly target photographers, and the upcoming morning’s 5am alarm. If only the #1 hobby of every single resident of San Carlos wasn’t driving around with massive car stereos with volume cranked to 11, blasting an eclectic mix of American 80’s hits and mariachi. No earplugs are good enough to block out Boy George songs played with tubas and accordions.

Zzzzz…. 5am BEEP BEEP uugh. Throw on a dry wetsuit, a warm waterproof trench coat, known in the biz as a “boat coat”, a warm hat, and jump in the truck to drive to the marina where we met our captain. With an old broken down Ford Explorer, he trailered the boat (with us in it) down a little dirt hill and launched us into the water. He went to park, and we were under way a full 75 minutes before sunrise. Full speed ahead, about 90 minutes to the mouth of Magdalena Bay, and out into the open ocean. It was then that we got a bit of news – the baitball action has been much, much further south than usual, and whereas that first 90 minutes is usually where we’d start looking for action, it would likely be another 2 hours before reaching our first bird sign. So yeah, each day of 10 days began with 3.5 hours of full-speed boating. And don’t even get me started about the 4 hour trip into the wind back each day! But let’s get to the good part, shall we?

Upon reaching Timbuktu middle of the Pacific Ocean, finally we’d start seeing frigate birds and pelicans – a sure sign there’s a massive school of sardines below, known as a baitball. I’m pretty sure if you asked the sardines, they’d say they really don’t like being called that. “What do you mean, “baitball”?!?” Anyway, when predator fish, such as the target of the expedition, the elusive striped marlin, find a school of sardines down deep, they push them up to the surface where they’re more easily corralled, and that’s where the birds get their chance to dive-bomb, which, of course, is what leads us to the action. Ideally, we’re looking for a “static” baitball, meaning the sardines are tightly packed and spiraling, rather than the school swimming for distance. But a static baitball all-too often attracts other predators which usually send the striped marlin running; the main culprit being mobs of California Sea Lions.

But this year, another unfortunate spectacle was unfolding. The guides & fishermen who work this region of the sea will see a single mahi-mahi (aka Dorado, aka Dolphin fish) perhaps once or twice in a season. But this year, they were everywhere. And on every single drop into the water, there were countless 25-40lb mahi decimating every baitball. And while this may sound awesome, when there’s rambunctious mahi, the comparatively-timid striped marlin stay away. It was explained to us that they were expecting warmer-than-usual water temperatures this season’s El Niño. And this is the speculation why the sardines were staying muuuuch further out than usual, and why plagues of mahi (who prefer warmer waters) were taking the place of the marlin this year.

We’d slide in the water, and most of the time, while snorkeling over to the action, the water visibility would be cut in half by hundreds of thousands of falling sardine scales, shimmering in the light (along with lots of sardine blood and guts!). The mahi (and sea lions) were just shredding through the baitballs so fast, that the 6-8” fish didn’t stand a chance, and the silvery scales exploded outward and slowly drifted down into the deep abyss. Now any other place, any other time, I’d be thrilled to photograph mahi. I’ve seen them in many other places including coastal Florida, the Pacific side of Costa Rica, Australia, etc., and the most I’ve ever seen at once was gathered around a drifting ghost net in Hawaii – about 15 individuals together. I also see little 1 centimeter larval-stage individuals when hunting for my Aliens Collection over the abyss at night. But here, I was seeing more than 200 at a time! And as cool as that was, I can’t photograph striped marlin when the mahi have taken over. But several times, I had to remind myself and my 2 frustrated friends that although the marlin were scarce, getting this opportunity to shoot mahi like this may well be a once in a lifetime experience, and we should “make hay while the sun shines”, or “make lemonade when the ocean gives us lemons”, or, “a mahi in the hand is worth two in the bush”…. I don’t know, I don’t do “sayings”, but what I do know, is that after half a lifetime at sea, Suzanne had still never seen even a single mahi, and I’ve only seen them just a handful of times. Let’s switch our brains’ gears, and shoot some awesome mahi photos while we can! And we did. And we did, and we did, and we did…. Most photos have thousands of white sardine scales looking like backscatter (backscatter is the term in underwater photography for when you improperly aim your strobe lights and illuminate all the water and it’s particulates in between the lens and the subject – it’s never desirable, and looks like snow in the photo). But technically this wasn’t backscatter, since I’m not using strobes. The scales are just unavoidable particulate in the water – the only options to avoid it, are to try to swim around to the other side of the baitball, get down lower, use a wider lens so I could get closer (I did indeed switch from the very-wide Nauticam WACP-1 to the ultra-wide Nikon 8-15mm fisheye for that precise reason), or simply just choose to not pull the shutter at all. Interestingly, myself and renown photog Brandon Cole were both shooting with new state-of-the-art mirrorless cameras – myself with the Nikon Z8, and Brandon with one of the new Sony’s. We both talked about how our amazing autofocus systems were, in a strange twist of fate, almost too good, as they would frequent rapidly change focus to land on the floating contrasty scales, rather than the baitball, which was ~3-5’ behind the layer of shimmer. Our friend Al Rector was shooting a still great quality, but now ~7-8-year-old Nikon D500, and Suzanne was shooting her awesome video through her trusty (but now a bit old) Panasonic Lumix GH5s. Both of those older systems actually did a better job of landing focus on the subject than our newer systems, whose AF is so good that it constantly picked up on the scales, just inches in from of our lenses. It seems that perhaps you can have too much of a good thing!

The Action:

Sardines aggregate together for spawning. One hopes they’ve been able to do a little horizontal no-pants romance dance before they’re discovered by the predators. Once they’re spotted by the striped marlin (or mahi, this year), they’re pushed up towards the surface, where the sea lions and birds join in the fray. And this usually continues until every last sardine is consumed. And within this dance of death lies my opportunity. The objective is to get the marlin to ignore me, but this is a delicate process. While the photographer’s instinct is to charge in and get the shot, patience & finesse are the most valuable skills here. When there’s a marlin (or 3 or 6), circling below, they’re easily scared off by the presence of another predator, such as me, or all-too-often this year, the mahi. So by hanging back 15-20’ or so, and watching the action unfold for a few minutes, the marlin can go about their natural hunting of the sardines, and begin to realize that I am no real competition nor a danger to them, mostly because a human swims at 5% their speed. Also, like in so many other interactions with large animals, a breath-hold freedive downwards is often viewed by the animals as an aggressive maneuver, so while playing the marlin game, that is a big no-no. But eventually, once the marlin gains confidence that I’m just a slow, clumsy onlooker, their feeding behavior resumes, and aside from getting the shot, now my primary objective is not getting skewered by their 2’ long bill.

It’s chaotic pandemonium, as the baitball desperately seeks out shelter. But in the open ocean, 40 miles from shore, often, the only shelter is me! The baitball at this point may still be 10,000 strong, or if it’s been picked at for the past hour, might be down to the last 50 or so sardines. When 50 panicked baitfish tightly cluster under your armpits, your first thought might be, “oh, how cute!”, until you remember that this is a survival strategy and three 7’ marlin close the 30’ gap between them and you in the matter of a fraction of a second, and their bill swipes just inches from my mask at a speed that makes Zorro look like a three-toed sloth. The objective is to get away from them, but it’s almost like there’s a magnetic attraction, and it’s easier said than done. But newer, fresher baitballs can be thousands, or tens of thousands of sardines, tightly packed like ….well…. sardines! Using their fishy 6th sense of the lateral line system to maintain a tight formation with only millimeters separating their closest neighbors, the idea is to look like a larger creature, reflect the sun with their shiny scales to dazzle & confuse, and to prevent a predator from singling out any particular individual. And when this panicked school decides to use me as shelter, the expanse of the open ocean immediately disappears, as the high-noon daylight sun turns to night, and the motion of a spiraling school gently starts churning and spinning me around. Nearly helpless to control the undesirable situation, I’d describe the physical sensation like washing a bunch of grapes in a bowl, but instead of your hands, it’s my entire body bumping against countless thousands of semi-soft, slimy, rapidly-moving grapes. With random spears slashing around my face!!!! The marlin see this as the perfect opportunity, and while I’m trying to escape the baitball, I’ll occasionally catch glimpses of a pointy marlin bill just missing my face. We’ll never know exactly how dexterous a marlin is when swiping, but being that I’ve almost been hit/stabbed over a hundred times, but never actually been touched by one, I’m going to say that they have a situational awareness that transcends what we humans can comprehend. I feel like through their lateral line sensory system and acute vision, they can sense precisely where I am, and avoid contact, while taking advantage of my presence to perhaps make their hunting even more efficient and accurate. Suffice to say, while I’m in the baitball, my objective is to get out, since I can’t shoot from within, and the best way to do that is a combination of top-speed swimming in random directions, twists, turns, and dives.

But as I mentioned earlier, every marlin encounter would soon be interrupted by the mahi mahi. At some point, one would show up, shortly followed by 3 more, and then 50. As soon as that would happen, the water would soon turn to a cloud of blood & guts, the thousands of falling reflective scales wound interfere with the shooting, and the marlin would be bullied into leaving. We’d usually get back into the boat and go searching for birds elsewhere. Frustrated, we’d bitch and whine a bit about how this has never happened in years past, and talk about what the El Nino weather pattern means, and if next year will be back to normal, or if perhaps we should wait 2 years. Nature is constantly throwing us a curveball, and it’s impossible to say for sure.

One of my favorite above-water sights from the boat has to be the rafts of pelicans and sea lions. Once they’ve reduced a sardine baitball down to the last fish, they’ll often take a rest to digest and warm up in the sun. Pelicans by the hundreds will lazily float, using their webbed feet to paddle into tight groups. Several times, I’d use my best breath-hold to swim underneath them to photograph their adorable webbed feet, but with my fisheye lens, that requires a distance of <1’, and time & time again, it proved more difficult than I had imagined, and ended up with more bird poop and bubbles than I did bird feet. But watching the California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus) from the boat, I was able to observe their method of thermoregulation known as rete mirabile (which is Latin for wonderful network). While floating, they’ll extend their flippers up into the air, and hold them at just the right angle to allow for maximum sun. The wonderful network is a system of arteries and veins in their extremities, which has very little insulating blubber or fur. By raising them out of the water, cold blood from their core passes adjacent to warm, solar-heated blood, and helps heat up their entire body. What a fun sight to see; 100+ sea lions all rafted together, with their flippers sticking out of the water, just lounging around with full bellies, over 40 miles from shore!

But the most unexpected and beautiful moments of the expedition happened when Earth’s largest predators suddenly made surprise entrances. On the 2nd day, we were working our acclimation period on a beautiful 10’ wide baitball and a few timid marlin, when out of the abyss flew in not one, but two 30’ long bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni brydei). With amazing stealth, they’d often be just 15’ away from the baitball before I’d notice them, and I’d marvel at how, even after multiple passes, I’d fail to see them coming more than 2 seconds from their prey. Strangely, they passed directly through the baitball multiple times, but never lunged through with their mouths agape, and this left me wondering why they might perform the hunt, but never actually eat.

However, several days later, we were filming a particularly messy and chaotic baitball being chewed apart by around 100 sea lions, hundreds of frigate birds, pelicans and gulls, and unfortunately, over 100 mahi mahi. I was ready to get out of the water because the chaos was too much for any marlin to stick around, and the visibility had been reduced to ~10-20 feet with all the blood & guts & reflective scales. But just then, from almost directly below, a dark form appeared, and got much bigger, very rapidly! With it’s mouth wide open and throat pleats completely flared, a 30’ humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) consumed the entire baitball in one giant gulp. Fortunately, I was in precisely the right place, aiming in just the right direction, and was able to rattle off a few shots. Unfortunately, with the cloudiness of the water from fish blood, and the quantity of sardine scales already in the water, my shots are far from world-class. Then on the final day of the expedition, I’m feeling beaten up, sore, cold, and lazy, and the birds and baitball had already attracted a frustrating number of mahi (meaning I wasn’t going to get my marlins). So I chose to stay on the boat and fly my drone over the baitball, while the ever-energetic Suzanne leapt into the water and swam straight for the chaos. I captured a few quick clips of some already-full pelicans and sea lions, and just while I was flying over to film the baitball from above, through a writhing mass of birds, another dark form appeared in the corner of my frame. As it closed in on the baitball, I said to the captain, “ohhhh, there’s a whale heading straight for Suzanne, but she doesn’t see it….she doesn’t see it….she doesn’t – OH NOW SHE SEES IT!!!” She turned around just in time to see another 30’ humpback lunge straight through the baitball, as I was recording the scene from ~40’ above. Arguably, she had the more desirable perspective, but when you look at her video from underwater, and my simultaneous video of the scene from above, it’s quite the amazing pairing! On the 4-hour ride home that evening, cold, wet, & sore, we saw blows of yet another pair of humpbacks, and they welcomed us into the water with them, dancing around us, and tracing lines around our bodies with their massive pectorals. Not long after, as we approached the murkier waters of Mag Bay with waning light at sunset, we repeated that same situation with countless Pacific white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquiden) who playfully zipped around us at mach-6. We’d freedive down, always making eye contact, spinning and frolicking, and they seemed to love the interaction as a break in their ordinary routines.

While a bit disappointed in the expedition’s lackluster marlin encounters, we finished with memory cards full of baitball action, just with sea lions and mahi replacing my intended marlin models. Still, I managed to snag a few energetic marlin images that I feel will print well. After returning from Mexico, I was only home for 5 days before leaving again, and I’m writing this ½ on a plane, and ½ at the next location. The mission is now to ensure the photos don’t get relegated to my dreaded “Images Unsorted” folder on my computer’s hard drive, where currently ~10TB of photos & video sit, unloved & unpublished, waiting for that thing that I believe people refer to as “spare time”. But I’m not built for desk-time! The ocean is calling me, and I must answer! Last month’s photos can wait – there’s more to shoot now!

-Gug