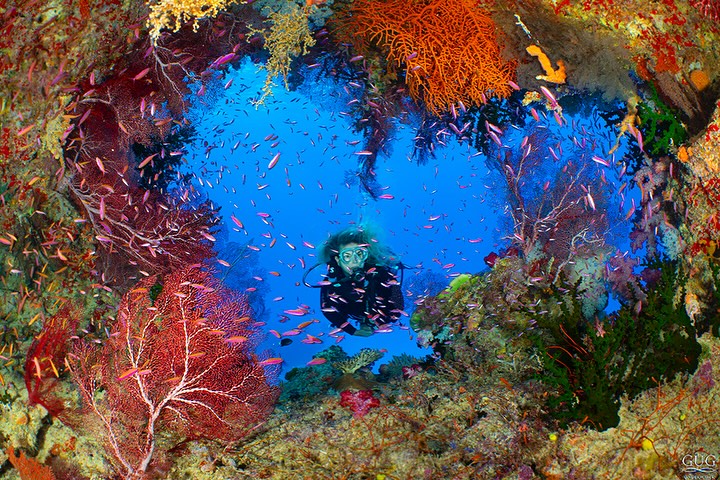

The island nation of Fiji earned it’s nickname among scuba divers decades ago by boasting one thing in greater abundance than practically anywhere else on Earth. The aptly-named, “Soft Coral Capital of the World” now attracts tens of thousands of divers per year, so how was I to create shots that match my vision, and stand out from the crowd? Like always, I had a plan and a vision, sketched out in several drawings, and most of them involved thick swarms of colorful anthias fish. But it took a combination of the right equipment, patience, animal empathy, and luck to bring it all together to get the shots this past October, and I’m so excited to share a few of the pics & stories with you here!

Getting to Fiji is actually a bit less complicated than many of my other South Pacific destinations. Just a quick hop across the USA to either San Francisco or Los Angeles, and there’s direct flights to Fiji’s capital, Nadi. From there, many divers catch a car or boat transport to their hotel, but Suzanne & I instead wanted to venture a bit further out, so we caught another tiny plane over to Taveuni Island, and a boat ferry across the strait to the far southeast corner of Vanua Levu to be closest to the legendary Rainbow Reef. Arriving at our tiny 3-room resort, we had a warm Fijian welcome from both the locals, and the island dogs! But there was not time to waste – I’ve always loved how my friends think it’s all a relaxing island vacation – while the resort manager was trying to give me a drink, I’m trying to focus on assembling my underwater camera systems! She suggested I relax and start diving tomorrow…ha! I told her I’d be ready in 45 minutes, and was hoping for 3-4 hours underwater before the sun set. I’m not sure if my local guide quite knew what to do with me & my eagerness!

But we’re here to talk about soft corals, so let’s get to it! First off – what is a soft coral? Soft corals of the genus Dendronephthya are stunningly beautiful corals that come in nearly every color of the rainbow from stark white, to red, blue, pink, yellow, orange, and purple. They look like branching bonsai trees with a central trunk attached to the sea floor. During times of high current, they stand tall and erect, and during slack current, they often shrink to 1/3 their full size and droop over like a sad glob of goo. While many other corals harbor zooxanthellae, soft corals are non-photosynthetic, so they’re often most successful in competing for space where sun-loving corals can’t grow, such as in caves or under overhangs, or at depths that the sun doesn’t effectively allow for photosynthesis. While there’s around 250 different species, most grow to a maximum of 20” tall, but they regularly form groups, and I was targeting the biggest, most prolific fields of dendronephthyas. A final fun fact, is their bodies contain countless 2-6mm spicules made of calcium carbonate which are used to give them the semi-rigid bonsai-like structure when they are inflated with water to their maximum size. You can see the spicules as little whitish internal spikes all throughout their trunks, whereas the fuzzy parts (think like the leaves on the bonsai tree) are countless little 3-6mm polyps, each containing 8 tentacles and a do-all mouth-butt opening, and each one a genetically-identical clone of the first polyp to start the colony. How cool!?!

On the morning of my first full day, I wanted to be taken to the most famous spot in the region – a spot that I’d seen in National Geographic and nature documentaries since I was a kid. And I wanted to get there early on because I knew I’d likely need attempts over multiple days to formulate my vision for my shot. This is partially because the best part of the White Wall is quite deep, meaning my time down there would be very limited because of both air supply, and nitrogen absorption. The soft corals on Fiji’s White Wall are actually light blue, and this smaller 6-8” species has grown on this vertical sheer cliff en masse. They’re a bit smaller and more spread out than some other species, so it’s not like a compete field, but it’s still a sight to behold. On the first attempt, my tank started at 2700 PSI (a full tank is 3000 PSI), so I was already at a disadvantage. With precious minutes ticking, I quickly descend down to the maximum depth of recreational diving at 130’, and then beyond. What an amazing feeling to be in a place of my childhood dreams! Imagine being a land-locked elementary school kid fantasizing about far-flung places like this, wondering if and how I’m ever going to get there! After a few short minutes composing a few preliminary photographs at depth, it was time to start the slow “multi-level” ascent used to minimize nitrogen absorption. Soon, I was no longer surrounded by my childhood fantasy, but rather looking at it 80’ below me, as I ascended up wards and upwards through a still-beautiful vertical cliff reef of hard stony corals and schools of fish. Fortunately, I planned this trip for the time of year that has the best water clarity for my extra-wide scenic photos, so I can still see every coral as I approach my shallowed deco stop depths. Because of the depth, a smart diver does this dive first, and then can do shallower dives through the day.

I talked it over with my guide, and I asked about a few things. First, I wanted the soft corals to be fully open, and that meant diving at peak high current flow. This not only adds another layer of complexity to the dive while trying to hold still to compose a shot, but also would cause me to use my precious breathing gas faster. Second, although I loved my guide, I shoot with a super-wide fisheye lens, and it was proving very difficult to compose a shot without him in it, so we made a plan for him to wait for me far above & behind, so I could shoot the wall in its entirety, and maybe on another day, I’d shoot him and/or Suzanne with the wall. And third, it all had to be done on a cloudless day. At that depth, there’s not much light, and since the wall is in constant shadow, I really needed full-sun. And over my 10 days there, I got two more perfect chances where high current, and cloudless skies cooperated. And on one of those days, I made my favorite shot of the wall with Suzanne as an unknowing model poised almost 40’ above me. As she filmed the White Wall with her powerful video lights, I used her silhouette to give a sense of scale & to tell the story my childhood dream.

But there’s so much more to this region than one magical dive site! I made sure to show my guide photos I had just taken on his reefs, as well as photos I’d shot years ago in other South Pacific countries, so he’d have a better idea of what I was after. Day after day, he’d take me to where he thought the current would provide the best patches of colorful soft corals and big schools of the anthias fish which often live among them. Rainbow Reef contains a series of dive sites, each one full of life. And while diving at slack tide is what most divers want for an enjoyable, relaxing dive, don’t forget, dendronephthya soft corals expand out and photograph best under ripping current, so I gave him full permission to put me in the most challenging conditions!

While in this region, I met a wonderful young woman named Makalesi who, in addition to working as a dive guide, has also recently finished her marine biology degree and has spearheaded a coral restoration program where she’s been transplanting coral fragments to an artificial structure. When the fragments mature, she transplants them back out onto Rainbow Reef and other areas that have been damaged by fishing, boat anchors, and other issues caused by mankind. I sat down to do an interview with her about her current and upcoming projects, and I’ll get it all edited some day soon, so be on the lookout for that in a future blog post.

After my time at Rainbow Reef, we boarded the same tiny plane to return to Nadi and meet up with the country’s only liveaboard dive vessel, the Nai’a. For the second phase of this adventure, our floating, mobile home would take us right to the very best reefs in the region. The guides would regularly ask me what I was interested in, and what I wanted to see, and I kept answering “soft corals and anthias!”. They’d roll their eyes, because that’s like, pretty much every site, and they wanted a better challenge. But again, I showed them some of my photos from the other Fijian region, and other countries, and made it clear that I was looking for some very special ingredients. After showing them my previous photos, and my idea sketches, the guides on the Nai’a understood exactly what I was looking for. One-on-one, realistic, open, & honest conversation with guides are often my secret weapon in creating images. But usually, that can only happen after I prove to them that I’m not a newbie, and won’t destroy their backyard to get a shot. That trust has to be built by example, not with words, and it goes both ways. Once I had their confidence, they saved me immeasurable time & effort by bring me privately to the spots that matched my visions. They’d point me to their secret spots, then leave me alone for an hour – my version of paradise!!!

After my time at Rainbow Reef, we boarded the same tiny plane to return to Nadi and meet up with the country’s only liveaboard dive vessel, the Nai’a. For the second phase of this adventure, our floating, mobile home would take us right to the very best reefs in the region. The guides would regularly ask me what I was interested in, and what I wanted to see, and I kept answering “soft corals and anthias!”. They’d roll their eyes, because that’s like, pretty much every site, and they wanted a better challenge. But again, I showed them some of my photos from the other Fijian region, and other countries, and made it clear that I was looking for some very special ingredients. After showing them my previous photos, and my idea sketches, the guides on the Nai’a understood exactly what I was looking for. One-on-one, realistic, open, & honest conversation with guides are often my secret weapon in creating images. But usually, that can only happen after I prove to them that I’m not a newbie, and won’t destroy their backyard to get a shot. That trust has to be built by example, not with words, and it goes both ways. Once I had their confidence, they saved me immeasurable time & effort by bring me privately to the spots that matched my visions. They’d point me to their secret spots, then leave me alone for an hour – my version of paradise!!!

I’ve spent decades learning the fine art of “fish psychology”. And making a school of anthias fish do exactly what I want them to do for the photo is a prime example. My visions for these photos mostly surrounded a school polarizing outwards from the soft corals in a burst of color against the perfect blue water. But to do that, I’ve spent perhaps dozens (maybe hundreds) of hours watching the back & forth “breathing” behavior of anthias. They’re both extremely bold and extremely skittish & flighty. As planktonivores, they feed by swimming up into the water column, facing into the current, and gobbling up anything that passes in front of their face. But that never venture more than ~5’ from the structure of the reef. As they’re plankton-picking, the school’s hundreds or thousands of sets of eyes are constantly scanning the horizon for danger such as black trevalley, coral grouper, or a huge, lumbering scuba diver with rushing torrents of scary bubbles pouring out of his head. If any of the thousands of hyperactive little buggers is spooked, using their lateral line systems to detect minute vibrations in their environment and in each other, they all get spooked, and a wave of fish simultaneously bolt for the cover of the reef. Luckily, they’re always hungry, so as soon as the predator fish passes (or after my bubbles rise away & dissipate) they begin to emerge from the cracks, one by one, and then in the hundreds. So photographing them is essentially an exercise in studying how they move in reaction to my movements and breathing patterns. Additionally, it’s interesting how my very presence often attracts larger predators (like the previously mentioned trevally and grouper), as those fish know how to use me as a tool – as the anthias are distracted by my presence, opportunities open for them to move unseen. I’ve mentioned plenty of times before, it’s my ethical responsibility as a wildlife photographer and filmmaker to not cause any damage to the ecosystem through my actions or presence….but that’s a topic I could write on for hundreds of pages…. And of course, like almost all of my photographs, I’m working with a fisheye lens, and am much closer than people would imagine – typically closer than 8” to my subjects, which means I’ve got to be as sneaky and quiet as a chuck of coral if I’m to get the anthias to be the best models they can be.

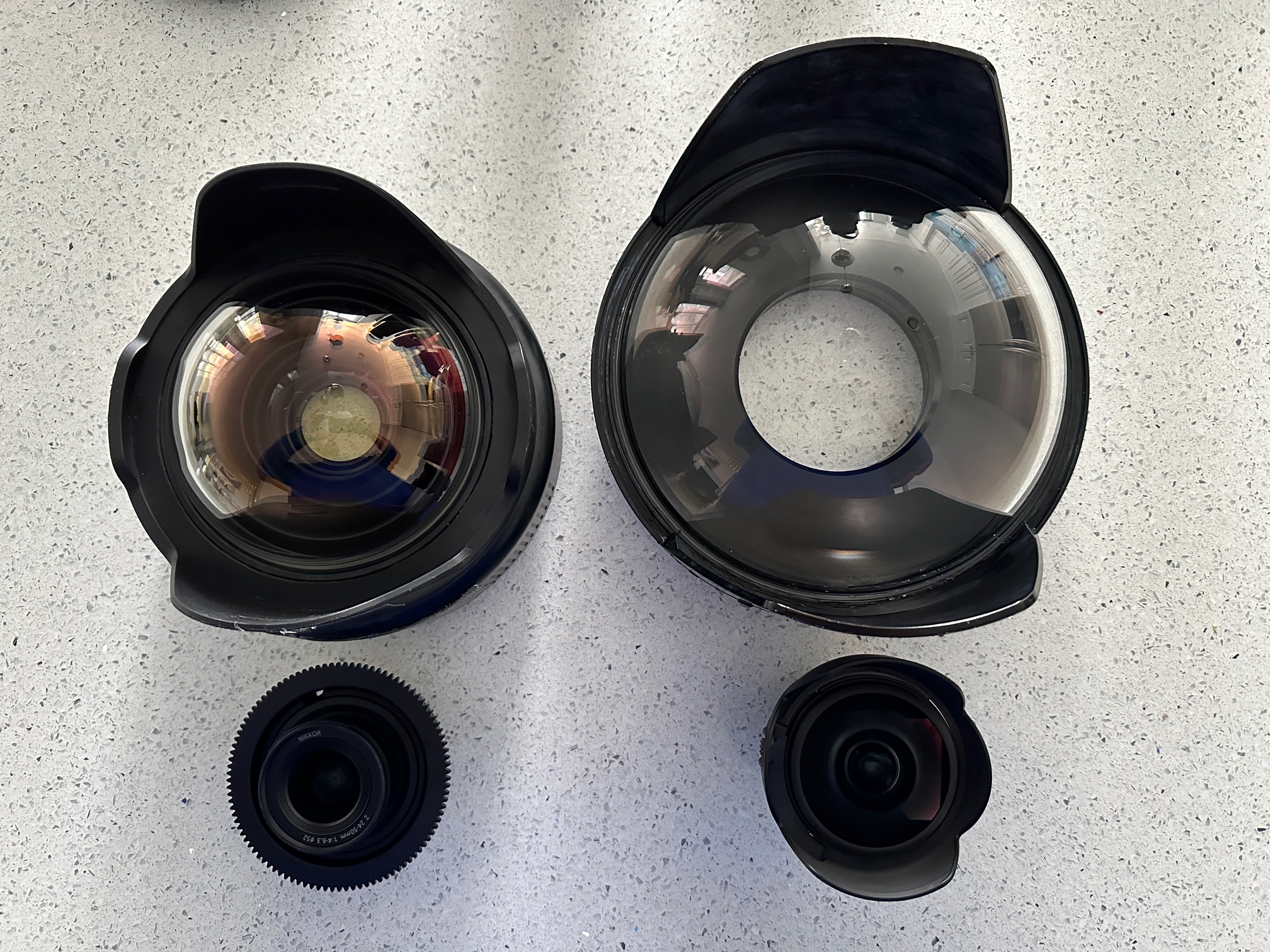

Speaking of lenses, on this trip, I was experimenting with the new Nauticam FCP, which stands for Fisheye Conversion Port. Rather than a traditional fisheye lens, such as the Sigma 15 or the Nikon 8-15 behind a 230mm dome port, I used the new, but relatively inexpensive 24-50 Z lens behind this new FCP. With it I can still focus on subjects that are literally pressed up against the port (just like with the dome port), but now have the added flexibility of zooming in for tighter portrait-style shots, although at decreased sharpness. I shoot with the philosophy that changing lenses all the time results in “jack of all trades, but master of none” results, so I shot with the FCP for every daytime dive of the trip until the very last day when I switched back to my trusty old 8-15 Fisheye behind the 230mm dome port, so I could do an apples-to-apples test of sharpness between the two setups. My opinion: the old-school fisheye lens behind the big dome produces images that are 1% sharper, but the added flexibility of the FCP’s zoom makes it a valuable tool in my arsenal that I have no intention of selling.

So yeah, it may sound weird to some people that I spent the entire several weeks in Fiji getting multiple variations of the same shot in different settings. With all that underwater Fiji has to offer, most underwater photographers would be much more varied in their approach. But as usual, I had my blinders on, and my eyes on the prize. All I cared about was soft corals with a big school of Anthias. And I got that – I got enough shots of that to last a lifetime! Three lifetimes! Okay, maybe I shot a few other scenic shots, like “Edge of the World” which is all hard stony corals, but still, I was pretty damn focused. But that still doesn’t make me stop wanting more. I see soft corals and anthias all over the Indo-Pacific, so it’s not like I won’t be shooting them again soon – but it’ll never compare to the sheer quantity and quality that can be found in Fiji – the aptly-named “Soft Coral Capital of the World”.